The History of the Pennsylvania Salt Industry

© Stephanie Hoover - All Rights Reserved

Required by the human body, salt is often described as the only rock we eat. Early settlers and Indians followed deer and other animals to their salt licks. These were retrieved and boiled to create table salt, but only a small amount was produced. As was soon discovered, however, the Allegheny Valley had more than enough salt springs to satisfy its own consumption.

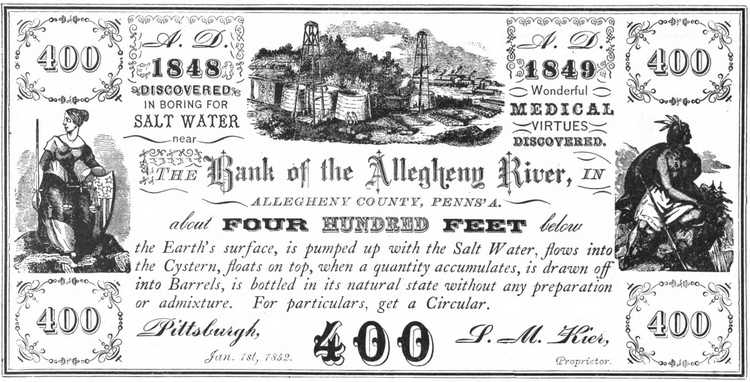

Oil found during salt drilling was thought to be a nuisance. One enterprising oil discoverer, Samuel Kier, decided that rather than toss it into the river, he'd sell petroleum as a "cure all."

In addition to its solid form, salt also occurs as an element of seawater, salt water lakes, and salt springs. While towns along the Atlantic coast could produce unlimited quantities of salt, the supply was too easily interrupted by war and other events. Pennsylvania's ability to produce salt inland proved invaluable. During the Revolutionary War, George Washington relied on Pennsylvania saltpeter to manufacture gunpowder for his troops.

Prior to and during the revolution, Western Pennsylvanians used pack horses to deliver salt from the east or from Kentucky. In the 1790s, when salt was scarce, buyers were more than happy to trade twenty bushels of wheat, or even a cow and a calf. By 1796 residents of the state's western counties realized it was cheaper to purchase salt from New York than eastern Pennsylvania. Soon five thousand bushels of salt were being shipped from New York's Ononadago Salt Works to Pittsburgh each year.

In 1798, a salt water spring was discovered along the Conemaugh River in Indiana County. Fifteen years later, William Johnson began manufacturing salt from this spring. As was the method of the time, wells were bored to a depth of 250 to 300 feet. This was a laborious process, at first performed by men, and later horses. Copper tubes drew saltwater out of the wells and into reservoirs constructed around the wells' mouths. The water was pumped to furnaces erected on-site. The furnaces were often powered by the coal found while drilling for salt. Thirty gallons of water were required to produce one bushel of salt. Johnson called his enterprise the Great Conemaugh Salt Works.

In 1814, nearby Armstrong County had its first salt well. Soon there were more than two-dozen salt works on the Conemaugh and Kiskiminetas Rivers producing 65,000 barrels of salt annually.

While the number of competitors in the salt industry grew, methods of transporting the salt improved. The Pennsylvania Canal enabled Allegheny Valley salt manufacturers to ship product west to nearby Ohio and east to Philadelphia and other large cities. So abundant were the salt springs in western Pennsylvania that the city of Pittsburgh itself, in 1829, boasted five. In July of 1833 the Pittsburgh Post Gazette reported that John Murray, while drilling near the bridge on the south side of the Monongahela River, struck a body of salt water at 627 feet. The water spouted 30 feet in the air. It produced 7,000 gallons of saltwater - equaling more than a dozen barrels of salt - per day.

Over time Pittsburgh salt manufacturers, with their improved machinery and methods, simply out-competed manufacturers in surrounding counties. The cheap rock salt that poured northward after the Civil War sealed the demise of many salt works.

All was not lost for salt miners, however. Samuel M. Kier, in about 1844, reported that his mines had started pumping dark, greasy liquid. Fearing that it might harm salt production, he and other salt makers drained the substance off into nearby waterways, including the Pennsylvania Canal. Boatmen complained that this was making their tow lines and decks slippery. When a hot coal was innocently tossed into the canal, however, the resulting half-mile-long fire demonstrated that this newly discovered petroleum presented opportunities that salt could never match.