The Yellow Fever Epidemic in Philadelphia

© Stephanie Hoover - All Rights Reserved

From Philadelphia's founding through the 1820s, yellow fever outbreaks occurred regularly. The deadliest years were 1793 to 1798. Though the strength of the disease varied with different attacks, the symptoms were always the same: yellow skin and eyes and "black" vomit.

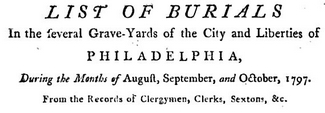

We know today that yellow fever is carried by mosquitoes. Prevailing theory holds that the fever was introduced to Philadelphia (then the nation's capital) in 1793 via slave trading vessels from West Africa. Infected passengers were bitten by domestic mosquitoes that transmitted the disease to Philadelphia inhabitants. A ship from Sainte Domingue (now Haiti) arrived at Philadelphia in June of that year. In August, the city witnessed 325 deaths and burials. In September that number climbed to 1,442. An estimated 5,000 people died over a five-month period in 1793 - roughly 10% of the population.

Doctors of the day referred to the outbreaks as "autumnal fevers." This corresponded with the lifecycle of the mosquito eggs: they were dormant during cold weather and hatched in the warmer, humid months. In October of 1794 noted physician Dr. Benjamin Rush reported:

Out of about thirty patients whom I visit daily, who are confined by bilious and intermitting fevers, twelve of whom have fevers of the highest or most inflammatory degree, commonly called yellow fevers.Rush's report, combined with those of other doctors, led the city's board of health to conclude that, since yellow fever did not appear to be contagious, Philadelphia citizens had little to fear. Nearby Baltimore, however, was experiencing an alarming outbreak. It was therefore recommended by the board that intercourse between Philadelphia and Baltimore be suspended. A committee of twenty persons was appointed to enforce this prohibition, and to insure that those entering the city posed no threat.

Philadelphians fled the city en masse hoping to escape "Yellow Jack" as it was nicknamed. Large numbers flocked to nearby Wilmington, Delaware, which ironically prospered from the tragedy. Any Wilmington resident with a spare room to rent found eager takers. Local stables and carriage houses were rented to Philadelphians in need of storage facilities. Local ships' carpenters were busy repairing and maintaining the Philadelphia vessels that now filled their harbors. Indeed, Wilmington seemed to have somehow evaded yellow fever - until 1798. In that year, a tenth of Wilmington's 2,500 residents died. The disease struck again in 1802, even after the city implemented rigid quarantines on both road and waterways.

Yellow fever revisited Philadelphia in 1795 and 1796 but in a weaker form than previous outbreaks. There were likely those who thought the disease was finally dying away. But only a year later, panic again ruled the city. Governor Thomas Mifflin called upon the College of Physicians to provide an assessment of the outbreak, as well as opinions on the best modes of treatment and prevention. On August 16, 1797 Dr. John Redman, college president, reported back that as many as a dozen persons had thus far died.

On August 17th Redman provided, among others, the following recommendations to combat the fever:

- "scrupulous attention" to street cleaning and flushing of guttersDaily death and hospital admission tallies appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette. August of 1797 saw 288 deaths, 141 of whom were children. Yet, by the beginning of November, the newspaper was reporting that "The city is once more itself. The greater part of the inhabitants are returned, the markets are full, and the usual intercourse has generally taken place."

- suspension of intercourse with the part of the city where the disease first appears

- removal of the sick and their families, and, removal of the uninfected from areas where yellow fever occurred

- suspension of merchants' business

- removal of vessels from wharves adjacent to outbreak areas

- quarantine of every vessel from the West Indies, areas south of Florida, and from the Mediterranean between the months of June and September

In the summer of 1798 the fever appeared again. It became especially virulent in August. Ninety-four deaths occurred during the first thirteen days of that month. Between August 14th and the 22nd 138 more deaths occurred. Another 234 died between August 22nd and the 29th. William Jones, president of the Board of Managers of the city's health board reported that "the malignity of the prevailing fever and its insidious approaches, are such as to resist the power of medicine, unless application is made in the first instance of complaint."

Once again people fled. By some accounts 50,000 of the 70,000 residents left Philadelphia. Of the 20,000 that remained, some reports indicate as many as 4,000 died. The suspension of publication of the Pennsylvania Gazette on August 29th makes exact counts hard to ascertain.

Thinking it was doing its residents a service, the city erected tents on the Schuylkill River for those wanting to leave highly populated areas. This only moved people closer to the source of the disease: the mosquitoes which carried it. Desperate for caregivers, a call went out to members of the public willing to work as nurses.

By December 1798 the yellow fever had once again faded away. Ward supervisors adopted measures to purify the beds, houses, and clothes of those who had been infected. In February of 1799 a far more effective measure was enacted: the introduction of large amounts of "wholesome water" into the city. Not only for consumption, this supply was to be used to flush "putrid and noxious" matter from the streets and sewers. Though they did not realize it, they were finally attacking yellow fever at its source: the standing water in which disease-carrying mosquitoes laid their eggs.

Comparatively minor outbreaks occurred in Philadelphia over the next two decades, but none as ferocious as those of the 1790s. ~SH